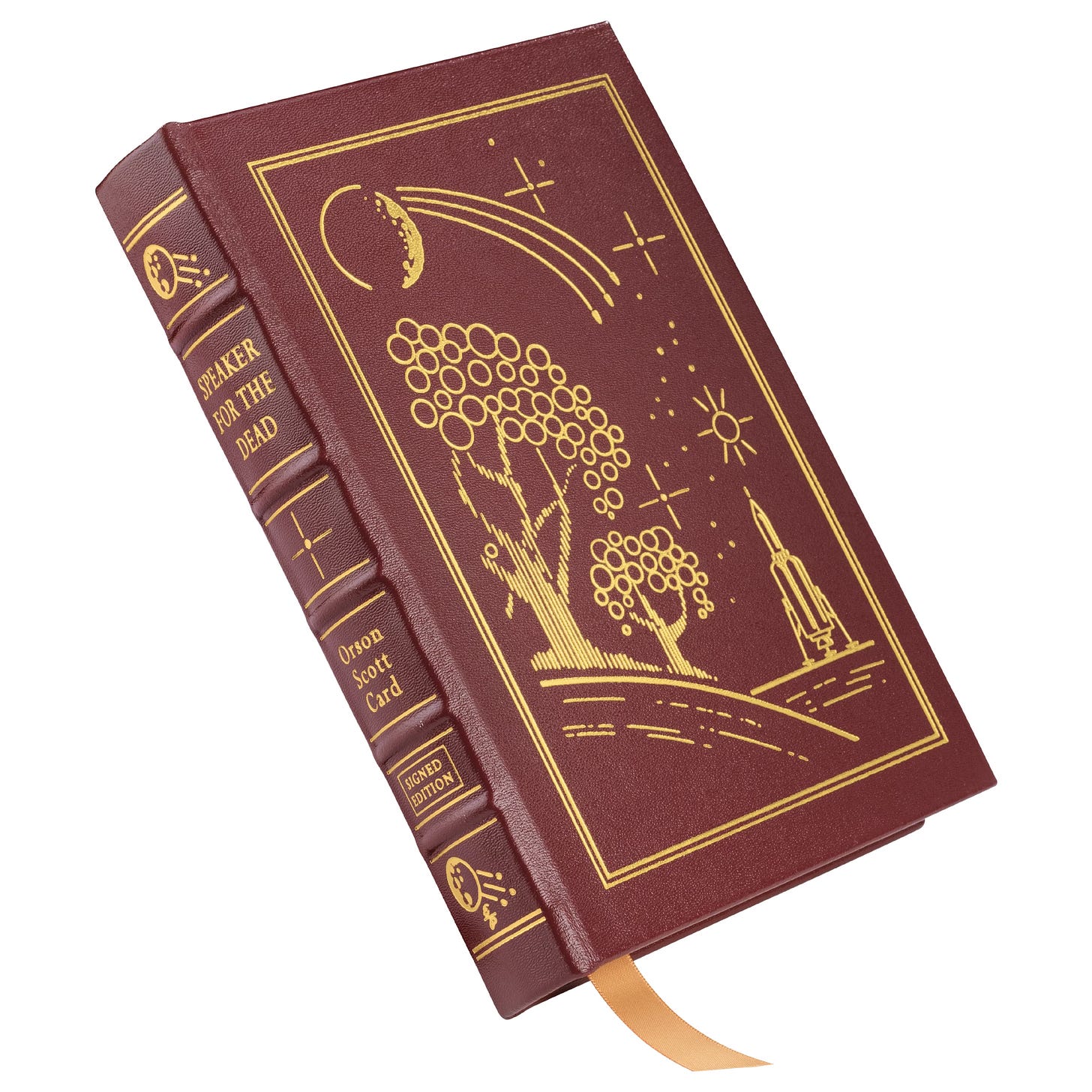

Speaker for the Dead

Orson Scott Card

You may be wondering why I chose this unique picture that bears no resemblance to the standard cover of Orson Scott Card’s amazing science-fiction novel, Speaker for the Dead. Let me explain. The books in the Ender Series—although commercial and critical successes—were given generic reused covers from a different sci-fi series that had enjoyed less luck…