“Newstalghia”

Two of my main fascinations are words and genre. So, when I come across a genre I don’t have a word for, my happy mind buzzes until it finds one. Longtime readers will recognize a couple: (all together now) Theatre of Being and bricomage. I have long been searching for a suitable word to describe my favorite type of film, which has a spiral structure centered around a complex theme, though the right word has eluded me. But today, I’d like to talk about another neologized genre I particularly love: newstalghia.

Before I describe what this word means to me –– and what works might fall into its orbit –– let me explain where I’ve pulled this term from. Our word “nostalgia” conjures up fond memories of a mythologized Golden Age (as all golden ages must ultimate be myths). Its emotional overtones are usually of the soft-and-fuzzy kind (one might say hygge or gezellig, depending on their cultural background). However, in Russian, “nostalghia” refers more to a heartsick longing for a dearly-loved homeland. (This actually hews closer to the Greek origins of the word: nostos, to return home, and algos, pain.) While this Russian term might serve us fine, in order to signal that I am talking about an aesthetic genre –– and to introduce the idea that our homeland is one we have not yet seen –– I have replaced “no” with “new”. Newstalghia, then, is art that seeks to evoke both the pain of our broken world and the confident longing for its promised renewal. It is, “In this world you will have much trouble, but fear not: I have overcome the world!”

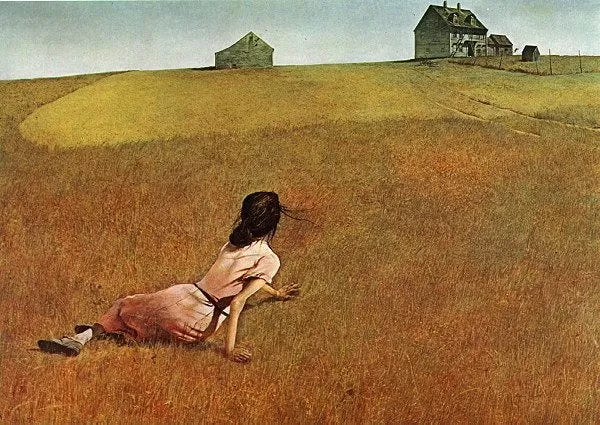

Certain works spring to mind immediately when I think of newstalghia. “Wayfaring Stranger”. Uncle Vanya. Christina’s World. It is this last work –– the achingly beautiful painting by Andrew Wyeth –– that recently set me on the path to identifying the tradition it springs from. A recent Facebook comment (I feel like that term needs a trigger warning these days) responded to my love of the painting with, “It’s so depressing!” (Forgive me, person I have never met, if I have misquoted you.) Such a thought would never have entered my mind! From another comment (“Isn’t she paralyzed?”), I began to understand why this evocative painting might strike someone as depressing. Yes, if one looks into the work’s origin, they will find that Wyeth drew inspiration from a real incident involving a woman who, without the use of her legs, would still wander her property.

A couple of red flags arise immediately for me, though. Do we really project so much more pity on those who (for example) cannot use their legs? I know that my heart and body are more distorted and crippled than Christina, who does not see her paralysis as prohibitive of her active engagement in nature and the exercise of her body and soul. I see this woman, and I envy her her strength and solitude and holy communion, not pity her as a broken thing. Secondly, why do we feel the need to read the image through an artist’s biographical statement? I am a firm believer that once a work is released by the artist, they are no longer bound together (connected perhaps, but not bound). Though I am aware of the story that led Wyeth to create his painting, it is no more than a footnote in the back of my head when I take in the profound beauty he has fashioned.

So, what do I see in Christina’s World? Yes, I see a recognition of fallenness. This woman is on the ground, after all, for whatever reason. Secondly, I see her intense longing for a home that seems at once far away and close at hand. Third, I notice the title’s invocation of Christ’s name. Fourth, I see the gorgeous line produced by the figure’s sightline and arm that suggests, in that vast prairie landscape, eternity. This is the most striking element to me: the way Wyeth has composed his image so as to bring a sense of immensity to the titular world. Not only does this immediately call to mind thoughts of Elysian Fields and the now-young, now-perfect woman running, laughing, through endless stretches of grass (I can thank Terrence Malick, in part, for that; his film Days of Heaven is inspired by the painting, and the overarching image of his oeuvre is the female form running through tall grass), it also reminds me how vast Christ’s world is –– and therefore, His atoning work. As the Sixpence None The Richer Song marvels, “Oh, the world is such a big place, and you have redeemed it––you have redeemed it all!” Finally, I see all of this channeled along the woman’s outstretched arm towards a truly homey place of belonging. (Perhaps, if you were not raised among rural fields and farmhouses like I was, the “hominess” is less obvious.) To me, this painting is an unparalleled elegy for a fallen world and paean to a coming home. To me, this is newstalghia.

Interesting